Talking to Kids About Death

As an elementary school counselor, one of the hardest parts of my job was talking to young children about death. It felt so unfair for a little person to bear such sadness. The loss of a mother. A father. A grandparent. A brother. A sister yet to be born. An aunt. A friend. There was not a year that went by or a school that I worked at, untouched by grief and loss. With experience, it became familiar, but never easier. A first-grade teacher once stopped me in the hall to thank me for being so direct and honest with her class. I had come in a few days earlier to teach my weekly lesson and the students told me their class pet had died.

“All living things die,” I replied, and held the space for them to share their feelings.

Through the pandemic, death has visited so many families. Explaining such a challenging concept is one of the toughest things parents have to do. There is no one right or wrong way to go about it, just as there is no right or wrong (or one) way to grieve. Ultimately, follow your own heart and instinct. You are the expert on your own child.

Here are some ideas to guide you through.

Use Books

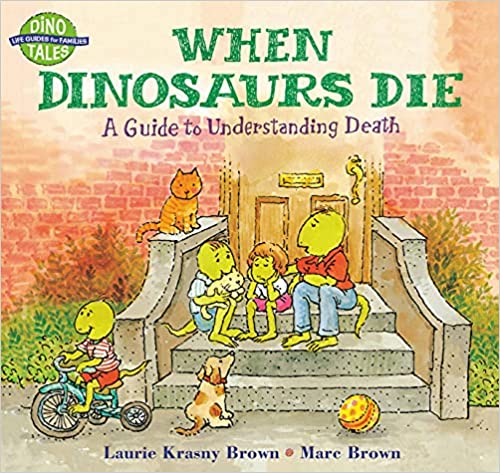

Books are a beautiful way to talk about death. My absolute favorites are Lifetimes and When Dinosaurs Die. I recommend reading these books to children starting at age 3. This is when they become aware of the concept and have questions. Sharing an explanation at a young age helps set the foundation for later, more personal situations.

“There is a beginning and an ending for everything that is alive. In between is living.”

~Lifetimes

Lifetimes is a great one to start with because it is a matter of fact, and uses examples in nature to help understand life cycles. I read this book slowly, a few pages at a time with toddlers and preschoolers, connecting their examples with ones in our own life. For example, on the page with trees, I like to pause and go outside to look at our trees and to touch them, reinforcing that the tree is alive. Pointing out the cycles of the seasons, as flowers bloom and die, brings that awareness to young children that life cycles are all around us.

When Dinosaurs Die has been the most helpful when talking about the different ways that people (and pets) die. I like to read the book slowly as well, making connections to their situation “this is just like grandpa” and as an introduction to all the different cultural customs that people have to mourn loved ones. This is a great way to share what you believe in your family and to reinforce your own value. Again, there is no right or wrong way.

“Every single living being has a beginning, a time to be alive, and then an ending, or death. During your lifetime, your body is busy doing its work. You breathe, move, eat, see, hear, touch, taste, smell, grow, talk, play, think, and feel. Yipee! You’re alive and a part of the world. “

~ When Dinosaurs Die

What Questions Do You Have?

When there is a death in a child’s life, grown-ups often want to protect them. However, children are good perceivers and poor interpreters, which means they are highly sensitive and intuitive. They observe and pick up everything…and yet they interpret it in a different way. If we DON’T talk about it, they will make up their own conclusions and interpretations. Children have an innate protective instinct to only absorb what they can. In this way, I like to ask THEM “what questions do you have?” and go from there, as opposed to making assumptions.

Mindfully listening, validating feelings without fixing them, and simply being completely present with them can be extremely therapeutic for children.

“I feel sad missing grandma, but also happy thinking about our time together last summer. How are you feeling?”

“I see you, I love you, and I am here with you.”

The Dougy Center has other great resources with developmentally appropriate activities to help children process their feelings. For example, they have sentence starters like:

The thing that makes me feel the saddest is …

If I could talk to the person who died I would ask…

Since the death my family doesn’t…

One thing that I liked to do with the person who died was…

Art and Play Therapy

Young children process and express feelings through play and art. I found it fascinating how quickly my students would “play out” their grief using art supplies, family dolls, and puppets. Children relax through play, and especially when they are able to direct and lead. You can play or draw along beside them, gently helping them to process using curiosity questions and mirroring by repeating a phrase they say back to them neutrally without adding any judgment. Here are some phrases to use:

Tell me more about…

What is this one saying or doing…

How is this one feeling…

What happened to this one…

I notice…

I see…

Memories

When a loved one dies, explain to your child that their memory will always live. This can be especially hard for grown-ups who fear that their child won’t remember. My own mother battled stage four breast cancer with three small children, and she says her biggest fear about dying was that we would not remember her. (She is now 74!) Help your child keep the memory alive by talking about the person, showing pictures or videos, or creating a memory box. Some families plant trees as a living reminder. I spent weekly sessions with a second grader who had lost her father unexpectedly, and we completed a page a week in this activity book. It was a beautiful guide to aid in processing, especially with the creative prompts, and a treasured gift to her other living parent.

Role Play: Take Time for Training

If there is a funeral or family gathering (post-COVID), take the time to prepare your child. Roleplay expected behavior (for example at a church, or another house) using stuffed animals and/or letting them be the grown-up and you be the child, then trading parts. Practice, explain what to expect, and prepare them for the long day (pack a backpack of toys, snacks, and books) or trip. Children are more willing to cooperate when they have relevance and understand why they need to be quiet, or wear itchy tights, or sleep in an unfamiliar place.

A beloved great aunt died a few summers ago in my family, making it the first funeral my children had been to. We spent time preparing them that a lot of the grown-ups would be crying, not because they were hurt, but because they were sad. We described what some of the customs during the ceremony would be, and made a plan for what to do when and if our 2-year-old became too squirrely. Children become anxious when they don’t know what to expect; the more you can give them a preview of the day, the more cooperative they are.

Take Care of Yourself & Model Self-love

If you are talking to your child about the loss of a loved one, this likely means you are also in pain. Give yourself the same compassion, grace, and comfort you give to your child, remembering there is no single way to grieve. It is a powerful opportunity to model how to talk about your feelings, and how to FEEL your feelings. Yes, this means you can share YOUR feelings, and model healthy coping skills like asking for hugs, going for walks, resting, journaling, breathing deeply, and sitting quietly. Reach out for help and take away any timelines for when you “should” start to feel better.

“Ultimately, follow your own heart and instinct. You are the expert on your own child.“

~Julietta Skoog

Here are some additional resources:

Sesame Street: Goodbye Mr. Hooper

Daniel Tiger: Blue Fish is Dead

NPR: Tips for talking to kids about death

Children’s Books to teach about death and grief:

Comments